The beginning of Bach’s Ouverture in B minor is built from sequences hidden in plain sight. Sequences are parts of music that are repeated an interval higher or lower. In this particular piece, single notes in the melody and in the bass are repeated sequencially, moving in parallel most of the time. Due to embellishments and octave displacement, the sequences might not immediately be clear to the ear, but once you’ve seen my analysis, you’ll be convinced that this page of Bach’s music is fundamentally based on sequences.

The Magic of Sequences

Before we delve into the piece, I’d like to reveal a few things about sequences. As you might know, each interval has an inversion. An interval is the inversion of another interval if, by using it in the opposite direction, you end up on the same note. For example: a C going up a Fourth goes to an F. A C going down a Fifth also goes to an F. Thus, a Fourth is the inversion of a Fifth and vice versa.

Sequences can make use of interval inversions. For example, a sequence that keeps going up by a Fourth might go like this: C, F, B, E. The same sequence of notes results from going down by its inversion, a Fifth. To keep such a sequence from ending up in an extremely high or low registers, both inversions can be alternated, for example: +4, -5, -5, +4. This way, a sequence can keep going for much longer. Technically, it could go on infinitely without ever leaving an instrument’s register.

Another cool property of sequences is that one sequence can contain another sequence when analysed at a different speed. To further explain this, let me first state that there are only six types of sequences. Those going up by a Second, by a Third or by a Fourth, in addition to those going down by a Second, a Third or a Fourth. Any sequence using an interval larger than that will be the inversion of one of these six types of sequences. For example, a sequence going up by Sixths is equivalent to a sequence going down by Thirds. It’s interesting to note that each of these sequences visits all root notes of the octave before ending up back at the original note.

Now what did I mean when I said one sequence can become another sequence at a certain speed? Let’s start with an example. Let’s say we have a sequence going up by Thirds, like: C, E, G, B, D. If we view each even note merely as an ornament between two other notes we get C, (E), G, (B), D. This is a sequence going up by Fifths! So a sequence of Thirds contains a sequence of Fifths! When skipping two notes each time, it contains a sequence of descending Seconds, and so on. Eventually, every sequence contains every other sequence when continuing like this for long enough.

In conclusion, when noticing these patterns in music, many sequences can be at play at once, because the types of sequences are so closely related. You will see in my analysis of the piece that sometimes a sequence of Fourths turns into a sequence of Seconds at a different pace, and it’s difficult to determine at what point this transition happens exactly. This is part of the magic of music!

All Types of Sequences

| Intervals | Example sequence |

|---|---|

| +2/-7 | C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C |

| +3/-6 | C, E, G, B, D, F, A, C |

| +4/-5 | C, F, B, E, A, D, G, C |

| +5/-4 | C, G, D, A, E, B, F, C |

| +6/-3 | C, A, F, D, B, G, E, C |

| +7/-2 | C, B, A, G, F, E, D, C |

| +1/-1 | C, C, C, C, C, C, C, C |

The Analysis

Now let’s look at the piece at hand: the first page of the first movement in Bach’s French Ouverture in B minor.

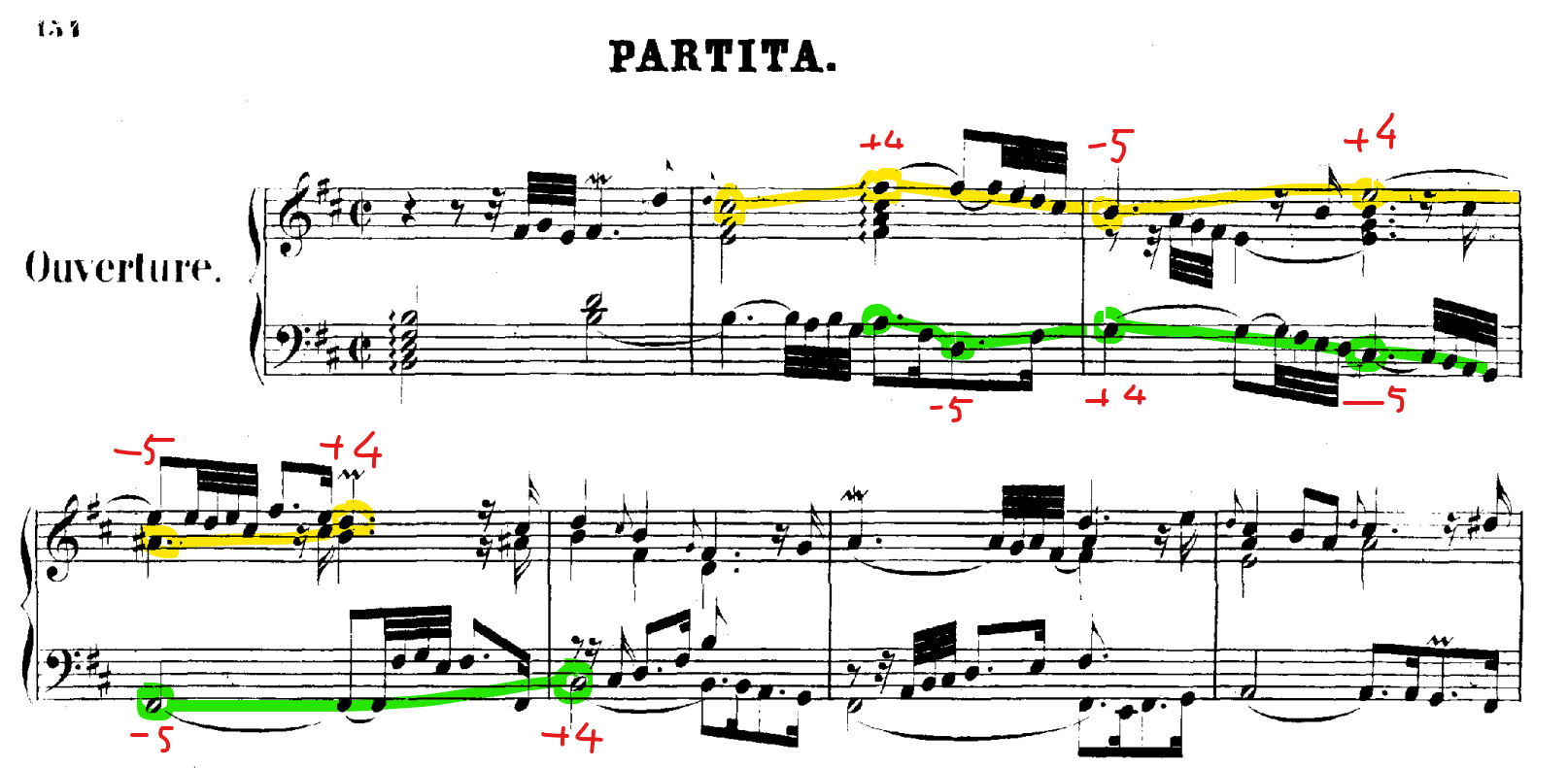

From the second bar a sequence of upwards Fourths and downwards Fifths starts in the melody. It is quickly joined by the bass performing the same type of sequence. The melody goes: C#, F#, B, E, A#, D. The bass goes: A, D, G, C#, F#, B. The bass and the melody maintain a relationship of Thirds and Sixths with eachother; an excellent basis for good counterpoint. In a way, the outer voices are moving in parallel, although the rhythm varies between the voices at some times.

After a cadence in bar 5, the melody starts a new sequence. This time the sequence is made up of rising Thirds. The melody starts from the D with which the previous sequence ended. It goes down by a Sixth before rising in Thirds. The notes in the melody are: D, F#, A, C#, E, G. It then quickly descends by a few Thirds, going G, E, C#, A#.

The bass joins in rising Thirds as well. It goes F#, A, skips the C#, but resumes with the E, forming parallel Thirds with the melody, except in the bar where C# was expected.

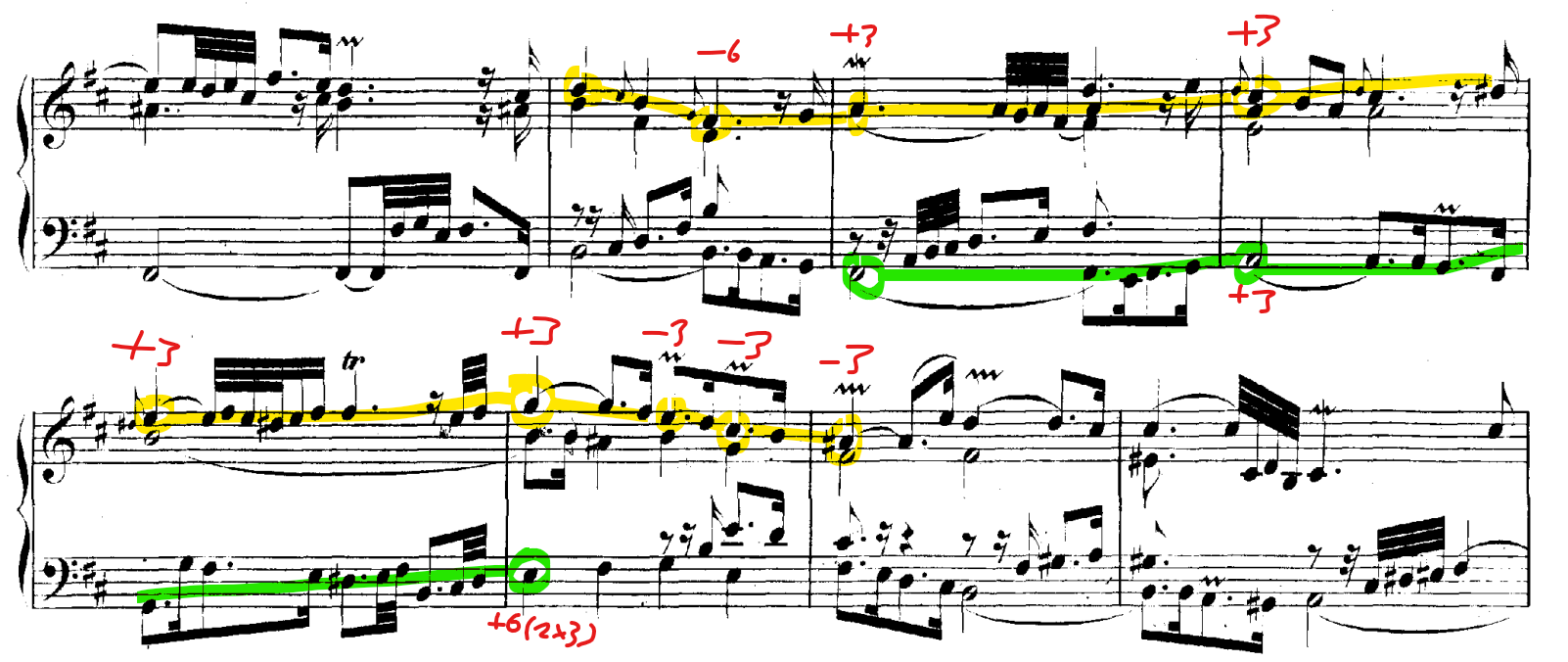

Then there is a long line of descending Seconds in the melody, accompanied by descending Seconds in the bass, which form 2-3 suspensions with the melody in the first few bars, and then just Thirds. The melody goes: D, C#, B, A, G#, F#, E#, and a bit later D. The bass goes: B, A, G#, F#, E, D, C#, and a bit later B.

Towards the end of the previous sequence, the sequence of descending Seconds morphs into a sequence of ascending Fourths and descending Fifths, remeniscent of the beginning of the piece. Finally, only the melody is still following this pattern, with the bass moving more freely as it prepares for the final cadence of the section. The melody goes: G#, C#, F#, B, E#, A, D, G#, C#, F#, and lingers on the final F# for a while. The bass goes: E, A, D, G#, C#, F#, B, and continues freely.

Reduction

Based on this analysis, I’ve crafted a simple reduction of this page of music to emphasize the sequences that are at the base of this composition.